An amputated worm regenerated into a double-head creature after spending five weeks aboard the International Space Station (ISS), scientists said.

Flatworms in space are helping researchers to study how an absence of normal gravity and geomagnetic fields can have anatomical, behavioural, and bacteriological consequences.

The research has implications for human and animal space travellers and for regenerative and bioengineering science.

Researchers, including those from Tufts University in the US, sought to determine how microgravity and micro-geomagnetic fields would affect the growth and regeneration of planarian flatworms (D japonica).

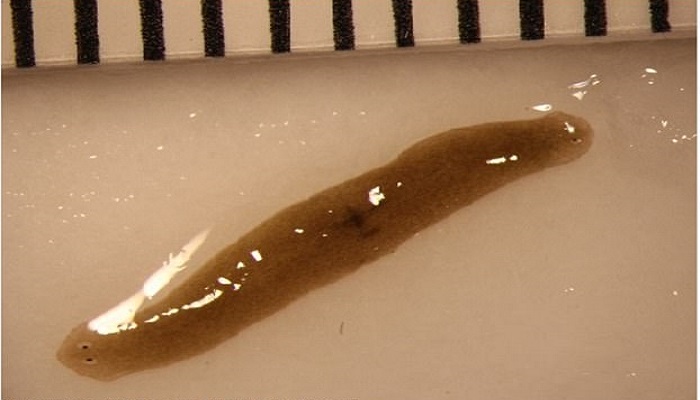

They discovered that one of the amputated fragments sent to space regenerated into a double-headed worm.

In more than 18 years of maintaining a colony of D japonica that involves more than 15,000 control worms in just the last five years alone, researchers have never observed a spontaneous occurrence of double-headedness.

Moreover, when they amputated both heads from the space- exposed worm, the headless middle fragment regenerated into a double-headed worm, demonstrating that the body plan modification that occurred in the worm was permanent.

Planaria are frequently used for studies because of their ability to regenerate amputated body parts.

“During regeneration, development and cancer suppression, body patterning is subject to the influence of physical forces, such as electric fields, magnetic fields, electromagnetic fields, and other biophysical factors,” said Michael Levin, a professor at Tufts University.

“We want to learn more about how these forces affect anatomy, behaviour and microbiology,” said Levin.

“As humans transition toward becoming a space-faring species, it is important that we deduce the impact of space flight on regenerative health for the sake of medicine and the future of space laboratory research,” said Junji Morokuma, research associate in Levins lab.

Researchers launched a set of flatworms into space in 2015. The flatworms were either left whole or amputated and sealed in tubes filled half with water and half with air.

They also created two sets of control worms. One consisted of live worms sealed in spring water in the same manner as their space counterparts and kept in darkness at 20 degrees Celsius for the same amount of time.

After the creturned to Earth, researchers prepared a second set of worms that were then exposed to the same changes in temperature as space- exposed worms.

After five weeks in space, the samples were evaluated upon their return. Researchers identified a number of differences between the space and terrestrial worms.

Apart from a rare worm sprouting an extra head, whole worms sent into space underwent spontaneous fission – division of the body into two or more identical individuals – while their earth-bound counterparts did not.

Researchers suggest that the worms had altered their biological state to accommodate the environmental change of being in space, reacting strongly to a return to normal aqueous conditions.

Post Your Comments