Japan and India, Asia’s second and third largest economies respectively, are achieving closer strategic convergence, a development that could reshape Asia. Since 2014, the two countries have elevated their ties to a “special strategic and global partnership,” shaping the security and economic architecture of Asia in an apparent move to counter the rising power of China.

The latest example of this partnership was a bilateral forum held on Aug. 3 in New Delhi to scale up development of India’s economically backward northeast region. Its goal was to “explore and expand” the role of Japan in spearheading infrastructure projects in this peripheral area that borders China, Myanmar and Bangladesh.

India’s northeastern states are populated by numerous hill tribes who have historically been neglected and left out of the country’s dynamic growth story. These states have suffered from armed separatist movements and persistent political instability, a reflection of ethnic conflict and poor governance.

Although global attention often focuses on secessionism and violence in India’s northern state of Jammu and Kashmir, India’s northeast region is no less an Achilles heel, with low per capita income, inadequate infrastructure and distrust between the local communities and the central government in New Delhi.

India also has had to contend with territorial claims by China affecting the states of Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, which have been heavily influenced by Tibetan Buddhism and are coveted by Beijing to consolidate China’s control over Tibet.

In previous decades, rebel movements in northeast India received Chinese funding and training. Today there are frequent troop mobilizations and incursion incidents across the China-India Line of Actual Control in the northeast sector. The latest standoff between the Indian and Chinese armies in the junction of the borders of Sikkim, Tibet and Bhutan testifies to the geostrategic value of this region.

It is no coincidence that India has invited Japan to help integrate the sensitive area. Indians remember fondly the military help that Japan gave to the freedom struggle of the nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose, who tried to overthrow British colonial rule toward the end of World War II. Indian politicians still refer to that period and emphasize the historical ties between the people of northeast India and the Japanese.

Japan has seeded a variety of projects in northeast India in such sectors as highways, power, water, sewage and natural resource management. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has assigned Japan a pivotal role in his vision of investing heavily to modernize the northeast so that it becomes a “gateway for Southeast Asia” and a stepping stone to India’s ambitious “Act East” foreign policy.

Japan as counterweight

Amid India’s perception of vulnerability to China’s superior military power and infrastructure development along the disputed LAC, the involvement of Japan, a regional rival to China, as an investor and builder in the northeast is a counterbalancing factor. From Tokyo’s point of view, adding northeast India to its basket of regional investments makes geographic sense because Japan already has a huge portfolio of development aid projects in neighboring Myanmar.

India, which fears increasing Chinese encroachment in neighboring countries, believes that Japanese financial and engineering strength is essential to mitigate China’s footprint in South and Southeast Asia. For instance, a Japanese-supported national highway system traversing India’s northeastern states would act as a catalyst to India’s delayed Kaladan Multi-Modal Transport Corridor for enhancing trade ties with Myanmar.

Modi and his advisers know that India alone cannot match China’s checkbook diplomacy and its regional transportation corridors. But they are convinced that India teaming up with wealthy Japan can help to some extent. New Delhi also holds Japan in high regard because it leads the Asian Development Bank, which is a crucial multilateral donor for the economic renewal of the northeast region.

Neither India nor Japan holds a favorable impression of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and both harbor suspicions of Beijing’s hegemonic intent. Modi’s call for establishing an Asia Africa Growth Corridor jointly with Japan is an undisguised effort to challenge BRI, create maritime connectivity routes in the Indian Ocean region that bypass China’s plans, while chipping away at China’s status as the main foreign player in Africa.

The state-owned Global Times of China has sharply criticized AAGC and warned that “if India and Japan design the corridor to deliberately counterbalance China’s BRI, they should think twice before rushing into it.” It added sternly that “India, for its part, should be particularly level-headed and guard against any overassertive plans that may go awry.”

Due to rising Sino-Indian border differences and their competition for influence in Asia, Modi is expected to play the Japan card even more assertively in the future. If the Japan-India partnership is trying to thwart China’s sway over Myanmar, it can do the same for developmental diplomacy in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal, three South Asian countries that China is actively seeking to wean away from India’s domain.

Reinforcing their claim of achieving a “global” partnership, Japan and India are also coordinating on promoting connectivity with the Iranian port of Chabahar. Tokyo is helping Afghanistan to gain access to Chabahar, while India has pledged its largest foreign financial investment of $20 billion for the port. With India’s land route to Afghanistan blocked by Pakistan, the Modi government views the Japanese role as critical for realizing India’s dream of reaching Afghanistan and Central Asia through sea routes.

Despite recessionary economic headwinds in Japan, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s “proactive diplomacy” and desire to work with and financially buttress Modi’s India creates an immense potential in presenting an alternative to a Chinese-led Asia. For Abe, India is the most advantageous vehicle to realise his dream of Japan “becoming a nation that participates actively in world affairs.”

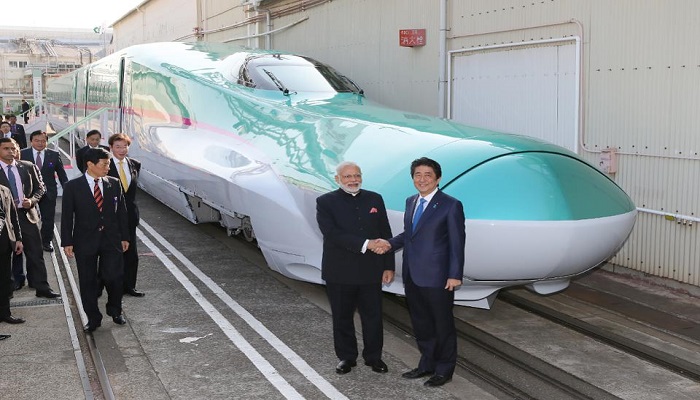

From the contentious waters of the South China Sea to continental Africa, an Indo-Japanese alliance in all but name has been formed. It includes maritime security (highlighted in the Malabar naval exercises that Japan co-hosts with India and the United States), infrastructural expansion (exemplified by Japan’s bullet-train contract to revolutionize India’s internal transportation network and its nuclear cooperation with India to improve power generation), and mutual economic gains (illustrated by Japan becoming the third biggest foreign investor in India and establishing 12 industrial parks there).

At a time of disturbing global change and geopolitical uncertainty and underscored by U.S. President Donald Trump’s lack of an Indo-Pacific strategy, the Japan-India axis is the most stable feature in the eyes of many regional observers — and looks set to grow.

Free-riding on the U.S. to restore the balance of power in Asia is no longer an option for Japan and India. Instead of looking westward for salvation, New Delhi and Tokyo have to rely on each other and assume responsibility to promote a multipolar Asia. From this perspective, the much heralded Modi-Abe embrace could produce limitless possibilities.

Post Your Comments