On the North Sentinel Island, a part of the Andamans exists one of the world’s greatest mysteries– the Sentinelese tribe.

While the rest of the world has seemingly moved into what can be termed as a modern civilisation, they are truly one of the last tribes of the world to live as primitive humans did, due in large part to their hostile, often violent, behaviour towards anyone who approaches the North Sentinel Island.

The island itself is one of the last remaining unchartered territories in the world! As such, what is known about the island and its inhabitants arises from observations made at a safe distance, usually restricted to the thin strip of the visible beach. The sporadic encounters with the tribe, more often than not, have been unsuccessful.

Described as “arguably some of the most enigmatic people on our planet,” in a report by The Seattle Times, the Sentinelese are believed to have inhabited the island for over 60,000 years!

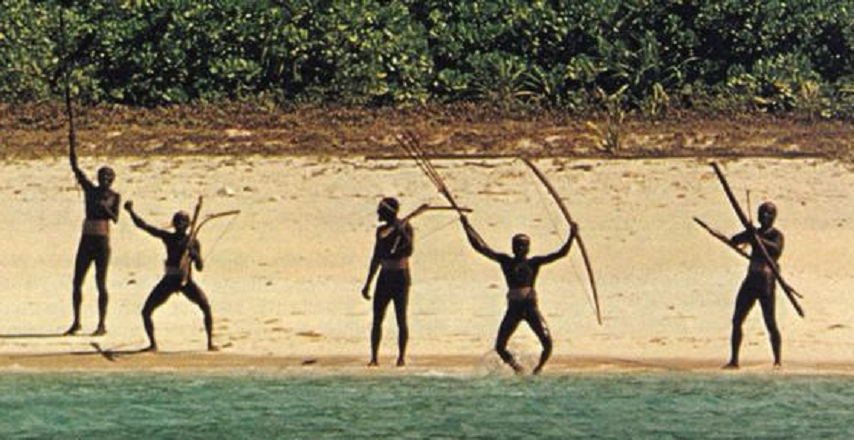

From what researchers have been able to decipher, the people survive on hunting, gathering, and fishing, and live in dwellings made of palm leaves. They also seem to have some access to cold-smithing techniques indicated by their array of weapons, such as harpoons, arrows, bows, and spears, which they have fashioned themselves.

While they wear no clothes, they do adorn their bodies with leaves, and wreaths fashioned out of plants. Their relatively short stature, dark skin, and peppercorn hair all suggest that they may have migrated from the African subcontinent centuries ago.

For a long time, they lived their lives seemingly undisturbed, partly due to baseless rumours that they were cannibals—until British invaders entered their territory in January 1880. Led by colonial administrator Maurice Vidal Portman, the invaders searched high and low for traces of the tribe. Eventually, they came across an elderly couple and four children. As per the British practice, to establish ‘friendliness,’ they kidnapped the family and took them to Port Blair. The parents soon passed away, possibly contracting diseases to which their body was not immune, but the children were loaded with gifts and returned to the island, where they quickly disappeared into the forest.

They were left alone after that, as the British turned their attention to the other tribes in the vicinity.

The first “contact” expedition, as it came to be known, was a failure—the tribe retreated into the jungle, and the party failed to engage with any of them. In the following expeditions, the Indian Navy vessel would anchor far from the island, and small boats would be sent up until a safe distance, where the party would then drop gifts into the water, to wash up on shore.

They would wait, sometimes for hours, to see if their gifts were accepted. Photographic evidence shows that on some occasions, the party was able to convince the tribe to leave their weapons behind and accept the gifts, but this would be short-lived, and soon, the party would be forced off the island with the threat of weapons and loud cries in a language which no one could understand.

Pandit and his team weren’t the only ones who tried. In 1974, a National Geographic team intent upon shooting a documentary about the Sentinelese tried to approach the island, bearing gifts, which included coconuts, aluminium cookware, miniature toys, and a live pig. Instead of a warm welcome, they were greeted with a shower of arrows, one of which pierced the director in the leg.

Post-1990, the tribe began allowing boats closer to the shore and would engage at times, in mildly friendly contact, accepting gifts and leaving their weapons behind. On one occasion, in 1991 when Pandit and his team arrived, the people came unarmed to greet them, climbed into their dinghy and were curiously touching everything.

He continues, saying, “But there was this feeling of sadness also—I did feel it. And there was the feeling that at a larger scale of human history, these people who were holding back, holding on, ultimately had to yield. It’s like an era in history gone. The islands have gone. Until the other day, the Sentinelese were holding the flag, unknown to themselves. They were being heroes. But they have also given up.”

It was a breakthrough, although the tribe did not allow their foreign visitors to stay for long. However, the government closed the expeditions in 1996, after the introduction of diseases to which their bodies were not immune had resulted in several deaths in a similar programme conducted with the Jarawas, another tribe in the Andamans.

With that, the tribe went back to their defensive ways. In 2006, two fishermen who were illegally looking for mud crabs got a little too close. The results were disastrous, leading to both of their deaths, and the helicopter sent to retrieve the bodies was continuously shot at with arrows.

helicopters which dropped food packages a mere three days after the event observed several of the members on the beach. They refused any aid that the helicopter attempted to provide and instead, shooed them away by brandishing spears and arrows.

So, despite the promises of modern civilization, why have these people continued to reject any contact with the outside world? More importantly, how long can they sustain themselves that way?

It is only possible to speculate, but there have been all kinds of theories. The obvious one is that the Islanders have everything they could possibly need to sustain themselves, from coral reefs teeming with fish, to a fertile jungle which harbours plants and other animals. Some believe that it is their tradition to protect their land from outsiders. They say that stories of past brutalities from “foreign invaders” have been passed down through the tribe, leaving them wary of any contact.

Others have even gone to the extent of saying that the islanders are hiding something within the depths of the jungle—that they may harbour a resource no one else has.

Talks of re-establishing contact have at times come into play and have till date been rejected mostly because of two reasons. Firstly, because the Sentinelese would be at risk of illness and even death, due to exposure to foreign agents. Secondly, their rejection of outsiders has been so potent that establishing a government against their will would take away their sovereignty.

Why shackle a self-sustaining society with the burden of modern civilisation? Why turn a free people into one in which an entire culture is lost, like the countless tribes before them?

If what we desire is an insight into their world, it is entirely possible, but we must be prepared to pay the price for the consequences. Until that time, the Sentinelese will continue to remain a mystery, one of the last truly free people on earth.

Post Your Comments