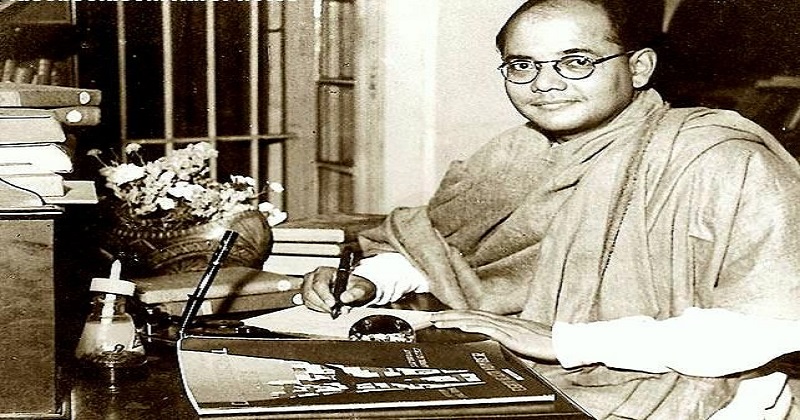

On January 23, 1897, in Cuttack, a boy was born to advocate Janakinath Bose and his devout wife Prabhavati Devi. At the time, they had no idea that their son would go on to become one of India’s greatest and most revered freedom fighters. With the call “Give me your blood and I will give you freedom,” he would one day challenge the might of an empire and inspire a nation to join hands to free itself from the shackles of imperialism. This boy was none other than Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, a brave soldier who devoted his entire life to his country so that his fellow countrymen could breathe the air of freedom, liberty and dignity.

The year was 1941. The day of January 16. From 38/2, Elgin Road, at the dead of night, a man quietly slipped out, speeding away in an Audi Wanderer W24 with a dream in his heart and a master plan ticking in his mind. Dressed in a long, brown coat, broad pyjamas and a black fez, Subhash Chandra Bose had just escaped from under the noses of the British police that had kept him under strictly-monitored house arrest.

As the British launched a nationwide manhunt for him, Bose quietly boarded a train from Gomo to Peshawar. From there, he made his way to Germany, travelling incognito with the help of his nephew Sisir Bose. In April 1941, India and the world were stunned when Germany’s Goebbel’s radio service announced: India’s most popular leader had arrived in Berlin to ask for Hitler’s help to deliver India from British rule.

Bose firmly believed that only an armed uprising could free India from the tyranny of the British. World War II seemed to provide an opportune moment. The UK was under attack from Japan, Germany and Italy. Guided by his belief “you must battle against iniquity, no matter what the cost may be,” his plan was to enlist external aid from these nations to crush British imperialism.

Once in Germany, Netaji had two objectives: the first, to set up an Indian government-in-exile, and the second, to create the Azad Hind Fauj, or “Legion Freies Indien”, a force of 50,000 Indian troops, mainly from Indian prisoners-of-war captured by Rommel’s Afrika Korps. Netaji wanted them to be trained to the highest standards of the German army so that they could form an elite fighting force which would enter India from Afghanistan at the head of a combined German-Russian-Italian-Indian army of liberation.

However, Bose’s two-year stay in Berlin was frustrating. Adolf Hitler, the German Chancellor, did not receive him for a whole year after his arrival in Germany. When he did, it was frosty, with Hitler giving no assurance about backing Indian independence. The Nazi leader had written, right there in his book Mein Kampf, that he, “as a German, would far rather see India under British domination than under that of any other nation.”In the end, a disappointed Bose decided to leave for Japan towards the end of 1942. By then, Imperial Japan had conquered Burma (now Myanmar). In its POW camps, tens of thousands of Indian jawans were held captured as the power cut through British colonies of South-East Asia. Those jawans were the army Bose had been looking for, and the reason for his new journey to Japan.

This time, his vehicle was not a motor car, an aeroplane or a train. Instead, it was a submarine, the Unterseeboot 180 (or U-180), skulking low in the icy water at the mouth of a Baltic fjord by Laboe, at the northern tip of Germany. The U-180 was a long-range sub with its forward torpedo tubes removed to create a hold for extra cargo. Its mission was to deliver diplomatic mail for the German embassy in Tokyo, blueprints of jet engines and other technical material for the Japanese military.

On February 9, 1943, its final freight arrived in a motorboat from the beach: two Indian passengers, Subhash Chandra Bose and Abid Hasan Safrani (one of Bose’s closest aides). The U-boat crew had been briefed that their passengers were engineers headed for occupied Norway, to help build reinforced submarine docks. As a result, Bose and Safrani were permitted to sit up in the sunlight, in the conning tower, for as long as they were in German waters. The submarine set a course that took it north along the Norwegian coast, then making a turn west towards the Faroe Islands.

The sea was rough, and the two Indians were often seasick. However, despite the airless confinement, it was an exhilarating moment for Bose. He was on the move once again, working towards fulfilling his dream of one day arriving in free Delhi. While his aide joked and groused with the crew, Bose spent much of his time reading, writing and planning how to deal with the Japanese.

At dawn on April 21, 1943, 400 miles southwest of Madagascar, the U-180 rendezvoused with a Japanese submarine and exchanged signals. As mountainous waves struck the German U-Boat under dark and rolling skies, its captain emphatically advised Subhash Chandra Bose against leaving the vessel to board the Japanese submarine.

Aboard the I-29, the Japanese captain Teraoka gave his own cabin to the Indian guests; it all felt, as Safrani wrote in his memoir, like “something akin to a homecoming”. Before they sailed, the Japanese crew shopped for Indian spices in Penang, Malaysia. They served Bose and Hasan a hot curry, to celebrate their crossing, and the birthday of the emperor in whose realm they had just arrived.

In the coming days, Bose would continue to Sabang on the tip of Sumatra, before moving to Singapore and finally to Tokyo. Here, he would take command of the Indian National Army, beginning the most admired chapter of his life. While he never fulfilled his dream of returning to a free Delhi, his aim to make it a reality never wavered. After Japan’s unconditional surrender in August 1945, Bose disbanded the INA with the words,

Post Your Comments