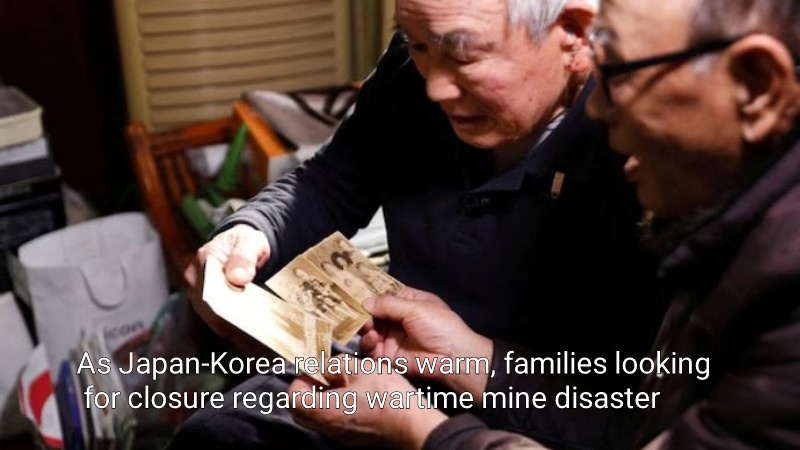

Four elderly Korean men bowed their heads in the direction of Japan’s Seto Inland Sea on a frosty February morning as the surf lapped close to their shoes.

They were paying respects to relatives who had been interred in a coal mine 80 years prior, among thousands of Korean bodies that had been dispersed throughout Japan as a lasting reminder of the colonial past that had long soured relations between the neighbours.

Families of the men recruited to aid Japan’s war effort in what is known as the Chosei mine during its 1910–1945 occupation of the Korean peninsula, however, see renewed diplomatic efforts to improve relations as a final opportunity for closure.

‘It is now or never,’ said Yang Hyeon, 75, whose uncle was one of the 136 Koreans and 47 Japanese who died in 1942 when a leaky mine off the coast of southern Japan collapsed and flooded.

‘Now that things are apparently getting better with Japan, I’m asking the two governments to think about us.’

Yang, who was present at the low-key ceremony in the town of Ube on February 4, is among the locals and family members pleading with the two governments to exhume the bodies and return the victims to their homes.

According to estimates from the South Korean government, the remains of up to 10,000 Koreans who died while performing forced labour, digging mines, or building dams are still in Japan. Japan claims to have found 2,799 wartime workers from Korea.

Since taking office last year, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol has sought to resolve historical differences with Japan and concentrate on shared contemporary threats like China and North Korea, both of which possess nuclear weapons. Attempts to repatriate them have been fruitless for more than ten years.

The elderly family members of the Chosei miners now have hope that they may still live to see the return of their loved ones’ remains after those overtures, which led to the first talks between the country’s leaders in years in September.

Post Your Comments