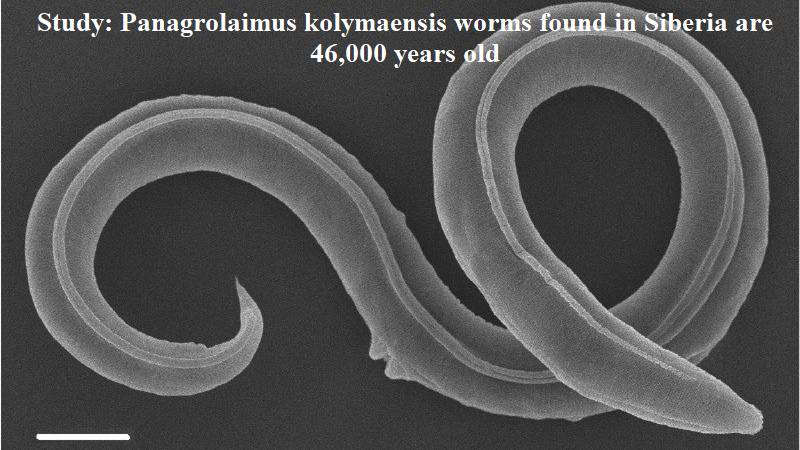

A recent research published in the journal PLOS Genetics reveals that the Panagrolaimus kolymaensis worms found in Siberia are believed to be 46,000 years old, based on the dating of the plant matter discovered alongside these nematodes. Despite their appearance as roundworms, nematodes have shown to be much more intriguing. The study also compares the survival mechanisms of the Siberian worms with those of another nematode species, Caenorhabditis elegans, which is commonly used as a model organism in laboratories worldwide.

Back in 2018, scientists had discovered and revived two types of microscopic nematodes in the Siberian permafrost, estimating their age to be around 42,000 years. These tiny creatures, now identified as a new species named Panagrolaimus kolymaensis after their habitat Kolyma River, have since become a subject of intensive research.

The survival abilities of the Panagrolaimus species have caught scientists’ attention, as they can withstand harsh environments involving desiccation or freezing. Cryptobiosis, the capacity of an organism to suspend its metabolism during challenging conditions, is at the core of these nematodes’ incredible resilience. If the nematodes are indeed as old as the study suggests, they would represent the most astonishing example of cryptobiosis.

The researchers involved in the study claimed to have successfully induced and terminated the dormancy-like state of cryptobiosis in the worms using “special preparatory cues.” However, genetic analysis of P. kolymaensis proved challenging due to their parthenogenic nature, allowing females to reproduce without the need for males. This makes obtaining the required number of worms for genetic analysis, roughly 2,000 to 4,000, difficult compared to the readily available lab species, C. elegans.

Despite the exciting findings, some experts remain skeptical. In 2018, outside researchers expressed concerns about possible modern contamination in the analyzed nematodes. Byron Adam, a biologist at Brigham Young University, is among those skeptical about the new study, emphasizing that the analysis merely proves the age of the nearby plant material, not the worms themselves. On the other hand, David Wharton, an emeritus professor of zoology at New Zealand’s University of Otago, acknowledges the work as impressive and interesting but points out that the freezing mechanism tested by the researchers is unrealistic as it involved drying the nematodes before abrupt freezing.

Post Your Comments