Avalanches in the Himalayas have not only caused an increase in fatalities but have also raised safety concerns for climbers, according to research.

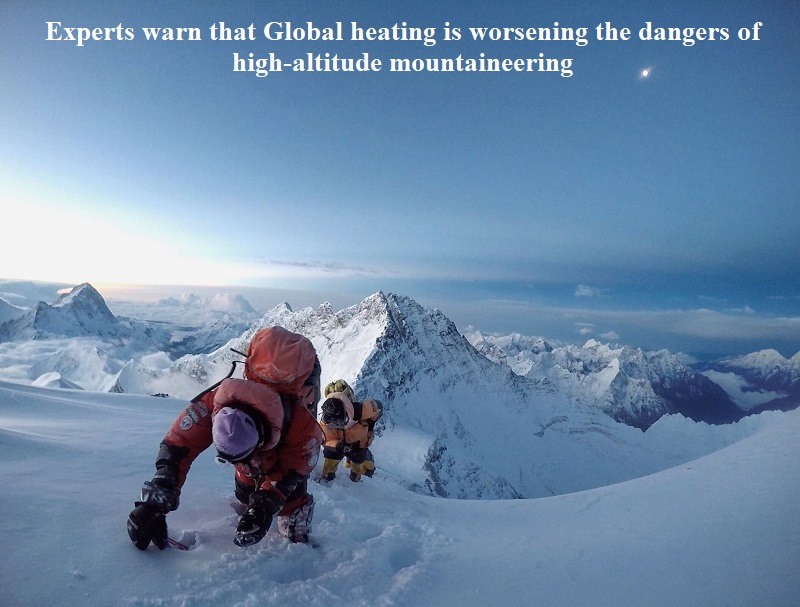

Experts are warning that global warming is exacerbating the risks associated with high-altitude mountaineering during the Himalayan climbing season.

Over the last five decades, at least 564 individuals have lost their lives due to avalanches while climbing peaks above 4,500 meters (14,770 feet) in the Himalayas, based on recent analysis. When focusing on the 14 peaks exceeding 8,000 meters and a few other significant climbing peaks above 6,000 meters in the Himalayas, the data indicates that at least 1,400 people have died in high-altitude mountaineering between 1895 and 2022. Of these fatalities, 33% resulted from avalanches.

Fatal avalanches on well-known peaks such as Everest, Ama Dablam, Manaslu, and Dhaulagiri are not a recent phenomenon; “mountains will avalanche. They have been doing it for decades,” says mountaineer Alan Arnette, as reported by The Guardian.

The climbing season in the central Himalayas, where most popular peaks for climbers are situated, typically occurs before the onset of the Indian monsoon season, which falls between March and May and then from September to November.

“The highlands of the Himalayas are generally protected from the impacts of cyclones originating in the Indian Ocean as the cyclones lose energy as they travel across the landmass,” explains Arun Bhakta Shrestha, a climate scientist at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, as quoted by The Guardian. “However, occasionally cyclones do impact the interiors of Himalayan highlands causing excessive snowfall and even causing loss of lives,” Shrestha added.

Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, points out that “In response to the rapid warming in the Indian Ocean, the monsoon has become more erratic, with short spells of heavy rains and long dry periods, and the cyclones in the Arabian Sea have increased in frequency, intensity, and duration and they are intensifying quickly both in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal,” as reported by The Guardian.

The significant impact of climate change is altering monsoon precipitation patterns and the frequency of cyclone formation, leading to disruptions in the once-predictable climbing season.

“In 1996, when we had that disaster on Everest [in which eight climbers died in a blizzard], it just absolutely cemented the fact that you have to consider what’s happening in the Bay of Bengal. If there’s a cyclone there, you have to watch it,” says Chris Tomer, a meteorologist and weather forecaster for mountaineering expeditions in the Himalayas.

He also notes that in the last five years, “four out of the five years we had to worry about something in the Bay of Bengal during the peak climbing season on Everest.”

Tomer, who has been providing forecasts for nearly two decades, adds that “Not that the weather wasn’t challenging 20 years ago, but it’s really been something to see the amount of snow on Manaslu and Dhaulagiri the last couple of years. They stand out with some of the most extreme weather over the last few years,” as per The Guardian.

The study was published in the European Geosciences Union.

Post Your Comments