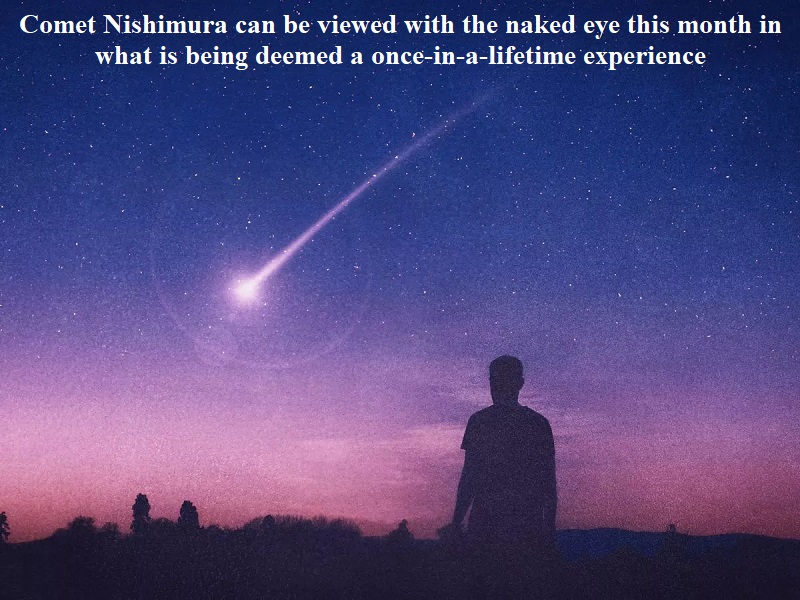

Comet Nishimura, which was only discovered last August, is currently visible to the naked eye and is expected to provide a once-in-a-lifetime celestial spectacle. On Tuesday, September 12, the comet will make its closest approach to Earth.

Comet Nishimura is hurtling through space at an astonishing speed of 386,000 kilometers per hour. According to Professor Brad Gibson, director of the E A Milne Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Hull in England, it is already visible without the need for telescopes.

To catch a glimpse of Comet Nishimura, observers should look east-north-east, toward the crescent moon and Venus, during the hour after sunset and the hour before dawn.

Professor Gibson emphasized the rarity of this event, noting that the comet’s 500-year orbit stands in stark contrast to Earth’s one-year orbit and the much longer orbits of the outer planets in our solar system. For comparison, Halley’s Comet, which last made a notable appearance in 1986, orbits the solar system every 76 years.

On September 12, Nishimura will be approximately 78 million miles away from Earth, offering an excellent opportunity for naked-eye viewing. Such sightings of comets without the need for telescopes occur roughly once a decade, making this event an extraordinary one in the field of astrophysics.

The comet is named after Japanese astrophotographer Hideo Nishimura, who discovered it while capturing long-exposure photographs on August 11, 2023.

Nishimura is expected to reach its closest point to the sun on September 17, coming within 27 million miles of it. There are concerns about whether it will survive this close encounter. Scientists are still in the process of estimating its size, which could range from a few hundred meters to potentially one or two miles in diameter.

Additionally, there is speculation that the comet may be associated with an annual meteor shower known as the Sigma-Hydrids, which occurs each December.

Professor Gibson explained that these comets are remnants of ice and rock from the early formation of the solar system nearly five billion years ago. As they approach the sun, the heat causes icy gases to be released, creating their distinctive tails. These comets also release tiny particles of dust and rock when they pass near the sun, and Earth intersects this debris every year, resulting in meteor showers.

Post Your Comments